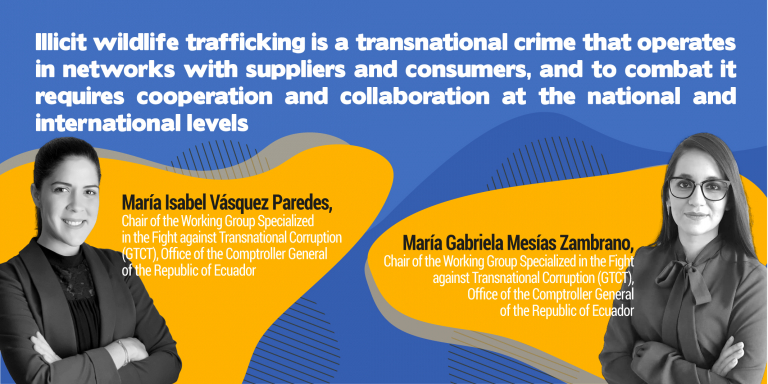

María Gabriela Mesías Zambrano

María Isabel Vásquez Paredes

Chair of the Working Group Specialized in the Fight against Transnational Corruption (GTCT)

Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic of Ecuador

The illegal wildlife trade has become one of the global environmental crimes that puts the natural assets of many communities at risk, potentially killing off species or bringing them closer to extinction and, in turn, it becomes the heart of what concerns the sustainable development of humanity clearly addressed by the 2030 Agenda adopted within the framework of the United Nations in 2015. This crime or offense is committed by anyone who extracts, collects, transports, commercializes or possesses wildlife species through capture, hunting or collection, in contravention of national and international laws and treaties.

This type of trafficking has a much wider and increasingly global scope, which threatens both the human population and ecosystems. In regions such as Latin America and Asia, this type of activity poses a risk to the conservation of wildlife ecosystems (Nijman, 2010). In this sense, it is important to note that Latin America is a region that is home to 40% of the world’s biodiversity and about 25% of endangered species, according to the Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)(Romo, 2019); biological wealth that attracts wildlife traffickers because, the rarer the species, or fewer of these that exist, the higher the price.

In recent years, the participation of organized crime in this chain has increased significantly, representing profits that subsidize other illicit activities and becoming a complex problem requiring urgent action (WWF/Dalberg, 2012). According to research, illicit trafficking has become a means of financing terrorist groups, guerrillas, civil conflicts, among others. In this regard, INTERPOL has studied how these organizations, when they are aware of the jurisdictions or lack of controls over the officials responsible, make use of this information to continue the trafficking as well as the process of money laundering, arms trafficking, among others (INTERPOL, 2020). However, as explained by WWF/Dalberg (2012, pp. 11-13), this trade becomes of greater interest due to the low risk and high profits compared to drugs, occupying fourth place in relation to organized crime. However, “drugs and human trafficking are receiving far more attention than illicit wildlife trafficking.”

As mentioned, this activity also triggers actions that put human health at risk; the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization has pointed out that 70% of new diseases that have emerged in humans in recent decades are of animal origin (FAO, 2013); the contagion of these diseases can occur through bites, scratches, contact with salivary or mucous excretions, contact with urine or feces and contact with blood fluids. Thus, the current global health crisis has rekindled concerns regarding the relationship between human health and illicit trafficking in wildlife animals. Although the host animal that transmitted the new coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) that gave rise to COVID-19 disease has not been identified with complete certainty, it has been recognized that the virus originated from a wild animal that was placed on the market in China. Therefore, the risk of illegal markets for the transmission of zoonotic diseases (any type of disease that an animal can transmit to a human being) is undeniable.

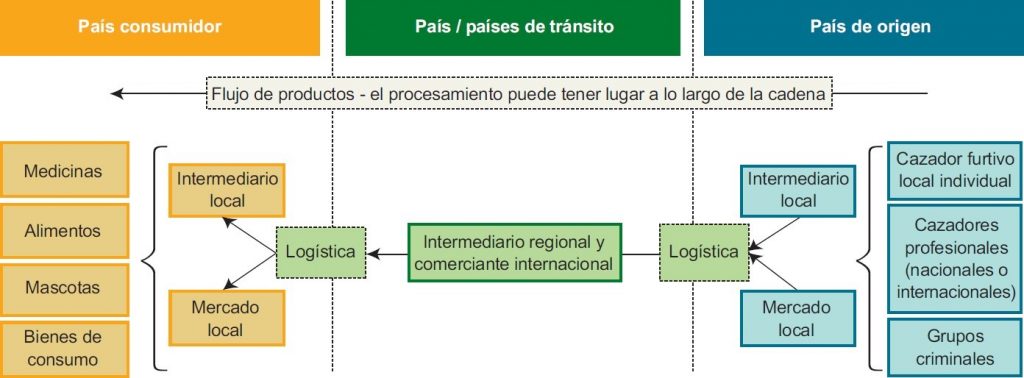

As a transnational crime operating in networks with suppliers and consumers, cooperation and collaboration is needed at both the national and international levels, between different government bodies, non-governmental organizations and citizens.

Governments in countries affected by the illicit trafficking chain should improve the rule of law, create or strengthen deterrence mechanisms, allocate resources to combat wildlife crime, specifically in strengthening environmental enforcement, trade controls and customs controls, and commit to a zero-tolerance policy on corruption. At this point, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wildlife (CITES) becomes a reference point for how to proceed with the sustainable trade in species, subjecting this activity to certain controls depending on the type of species to be traded.

Figure 1 Wildlife trafficking Value Chain

Taken from WWF/Dalberg The Fight against Illicit Wildlife Trafficking (2012, p. 11).

Faced with this reality, Supreme Audit Institutions can collaborate in the process of strengthening the environmental governance of countries, both at the level of effective external control of public funds intended for the protection and safeguarding of endangered species, and in the provision of good practices to audited entities in the environmental field with the aim of improving their operation. Likewise, this discussion, carried out at the State level, requires the involvement of these entities in order for compliance with existing controls and so that the prevention or mitigation system can highlight corruption problems.

In this regard, within the Latin American and Caribbean Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions, the Working Group Specialized in the Fight against Transnational Corruption (GTCT) worked with the financing of the German Cooperation – GIZ, in a consultancy to visualize and strengthen the role of Supreme Audit Institutions in the prevention and/or mitigation of the effects of corruption in the commission of environmental crimes with a focus on illicit wildlife trafficking. This consultancy culminated in a webinar held on August 19, 2020, where, in addition to presenting the results, representatives of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) shared their views on the role of SAIs in improving environmental control and highlighting the nexus of crimes such as illegal species trafficking with transnational acts of corruption. Furthermore, inter-institutional and international cooperation became more evident in that area as a means of combating such crimes.

Bibliography

FAO. (2013). World Livestock 2013 – Changing disease landscapes. Rome.

INTERPOL. (2020). Wildlife Crime. Retrieved from https://www.interpol.int/Crimes/Environmental-crime/Wildlife-crime

Karesh, W., Cook, R., & Newcomb, J. (2005). Wildlife Trade and Global Disease Emergence. doi:10.3201/eid1107.050194

Nijman, V. (2010). An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia Vincent Nijman. Springer. doi:10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4

Romo, V. (2019, October). Latin America recognizes wildlife trafficking as organized crime. Chinese Dialogue. Retrieved August 14, 2020, from https://dialogochino.net/es/sin-categorizar/30761-america-latina-reconoce-el-trafico-de-vida-silvestre-como-crimen-organizado/

WWF/Dalberg. (2012). Combating Illicit Trafficking in Wildlife: A Consultation with Governments. Retrieved from http://awsassets.wwf.es/downloads/wwffightingillicitwildlifetrafficking_spanish_lr.pdf

About the authors

María Gabriela Mesías Zambrano is an attorney with the Courts and Tribunals of the Republic of Ecuador at Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil. Master of Environment, Human Dimensions and Socioeconomics at Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Diploma in Environment and Sustainable Architecture from Universidad de Salamanca. Due to her academic training and experience in Environmental and Animal Law, she has had the opportunity to provide legal advice to both the public and private sectors regarding the protection of rights of nature and urban and wildlife animals. She has been visiting professor in Environmental Law and Agrarian and Natural Resources Law at Universidad de Guayaquil (2017-2018), Ecological Law and Law of Mines and Hydrocarbons at Universidad Tecnológica ECOTEC (2016-2017), professor at the training event “Environmental Crimes” organized by the Directorate of the School of Prosecutors of the Office of the Attorney General. She currently serves as the OLACEFS liaison of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic of Ecuador.

María Isabel Vásquez Paredes has a degree in Political Sciences and International Relations from Universidad Casa Grande. Master’s degree in International Relations with a specialization in Security and Human Rights from FLACSO. Fellow of the Program Management Research Trends: Nurturing Innovation of the UAM and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. Fellow of the Program for the Strengthening of the Civil Service in Latin America. Supervisory expert of the National Coordination of International Affairs of the Office of the Comptroller General of Ecuador. Within the framework of the Working Group Specialized in the Fight against Transnational Corruption, she coordinated the consultancy of illicit wildlife trafficking in Latin America and the Caribbean, an activity that was financed by the German Cooperation – GIZ and executed by the environmental expert, María de los Ángeles Barrionuevo.